Autosomal recessive mutations often result in the retinal cell missing an important genetic instruction, leaving the cell struggling to do its job.

Autosomal recessive conditions happen when both of the affected person’s parents each carry only one faulty copy of the gene. They experience no symptoms as their healthy copy of the gene can compensate. However, the affected child ends up inheriting two faulty copies, one from each parent.

The parents are sometimes referred to as unaffected carriers and probably did not know that they were at risk of having an affected child. The condition can seem to crop up out of the blue in the family, having not appeared at all in previous generations. Autosomal recessive retinal disease can often be fairly severe, with symptoms beginning in infancy or early childhood.

A genetic counsellor can talk about family history with you and try to understand whether or not your family is affected by autosomal recessive inheritance. A genetic counsellor can also talk about genetic testing with you. A genetic test can often find out exactly which gene is causing the problem and confirm the inheritance pattern. Genetic testing and Genetic counselling, explain more about how to access these services.

What are the risks to my children if I have an autosomal recessive condition?

If you are living with sight loss caused by an autosomal recessive condition, you will definitely pass a faulty copy of the gene on to each one of your children. However, if your partner has two healthy copies of the gene, which is likely, your children will also inherit one of these, meaning that they will be unaffected carriers. Your partner is less likely to have two healthy copies of the gene if you are related to them other than just by marriage, for example if you are cousins; in this case, your shared family history increases the chances of them carrying the same faulty gene.

A genetic counsellor will be able to explain the risks to your children in more depth. Your GP or ophthalmologist will be able to refer you. See Genetic counselling for more information.

What are the risks to future children if I already have one child with an autosomal recessive condition?

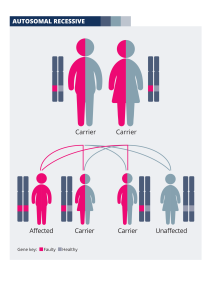

If you already have a child with autosomal recessive sight loss, for each following pregnancy with the same partner there is a one in four (25%) risk that the new baby will also inherit the condition. There is a one in two (50%) chance that the new baby will be an unaffected carrier, and a one in four (25%) chance that the new baby will not inherit the faulty gene at all. Gender is not a factor. The diagram shows how the faulty gene might be passed on and the possible outcomes for children.

If you already have a child with autosomal recessive sight loss, for each following pregnancy with the same partner there is a one in four (25%) risk that the new baby will also inherit the condition. There is a one in two (50%) chance that the new baby will be an unaffected carrier, and a one in four (25%) chance that the new baby will not inherit the faulty gene at all. Gender is not a factor. The diagram shows how the faulty gene might be passed on and the possible outcomes for children.

A genetic counsellor will be able to discuss risk with you in more detail, and, if you are planning a pregnancy, can also talk to you about the possibility of accessing testing during pregnancy or reproductive technology such as pre-implantation genetic diagnosis. Ask your GP or ophthalmologist for a referral. See Genetic counselling for more information.

Research into treatments for autosomal recessive retinal disease

Because many recessive conditions are the result of genes failing to provide instructions for a properly working protein, in some cases it may be possible to overcome the problem by injecting healthy copies of the gene into the back of the eye; this is known as gene replacement therapy. Retinal cells can use these healthy genes to produce normal protein, restoring function and enabling vision to be maintained or even improved. This is the principle behind Luxturna, the gene therapy available on the NHS to treat Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) caused by mutations in the RPE65 gene.

Another possible approach is to put a molecular “patch” over the faulty piece of genetic code, enabling the cell’s protein-building machinery to skip over it and still build a functional protein.

Other therapies are being investigated by researchers, but it is important to bear in mind that some of these are specific to particular genes; they will not all work for all autosomal recessive retinal conditions. Some loss-of-function mutations are harder to remedy than others, perhaps, for example, because they cause structural defects very early in the development of the eye. Genetic testing can provide information about the specific gene causing a condition, which may open up choices about future treatments or research participation. See Genetic testing.