In lower vertebrates, such as frog and newts, the eye is able to repair itself after injury. Unfortunately, the human retina cannot repair itself. The mature photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelial cells are unable to divide and produce replacement cells in the event of cell death.

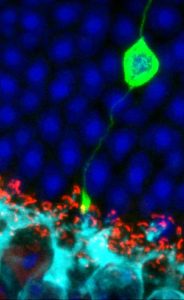

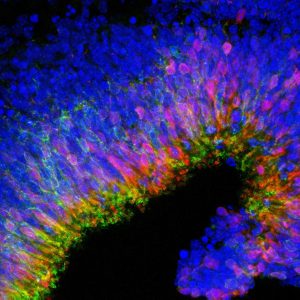

Stem cell therapy for the eye involves taking either the stem cells themselves, or retinal cells which have been derived from stem cells, and transplanting them into the retina. The aim is that these cells will then replace damaged areas of the retina and start functioning as the original cells would have done to restore aspects of sight. Stem cells are currently under investigation in early phase clinical trials to determine their potential to repair areas of the retina where cells have otherwise been damaged or lost due to progressive retinal degeneration.

Should I go abroad for stem cell treatments?

Types of stem cell

Different stem cells exist at various time points during an individual’s lifespan, from conception to old age.

Broadly speaking, embryonic stem cells have the capability to generate any cell type in the body, while adult stem cells are often restricted to generating a certain tissue type e.g. heart muscle cells or liver cells.

More recently, scientists have found ways to turn an adult cell (usually skin) back into an embryonic-like stem cell. These are called induced pluripotential stem (iPS) cells and are playing an increasingly important role in many areas of medical research.\

iPS cells derived from the skin of somebody with inherited sight loss will contain the mutation that caused their retinal condition. If these iPS cells are persuaded to develop into retinal cells in the lab, researchers have an ideal cellular model for studying disease processes and experimenting with new treatments.

Gene editing techniques could be used to take this into clinical use, by correcting the mutation in the iPS-derived retinal cells and then transplanting them back into the eye to restore the damaged retina. However, the effectiveness of this approach has yet to be established.

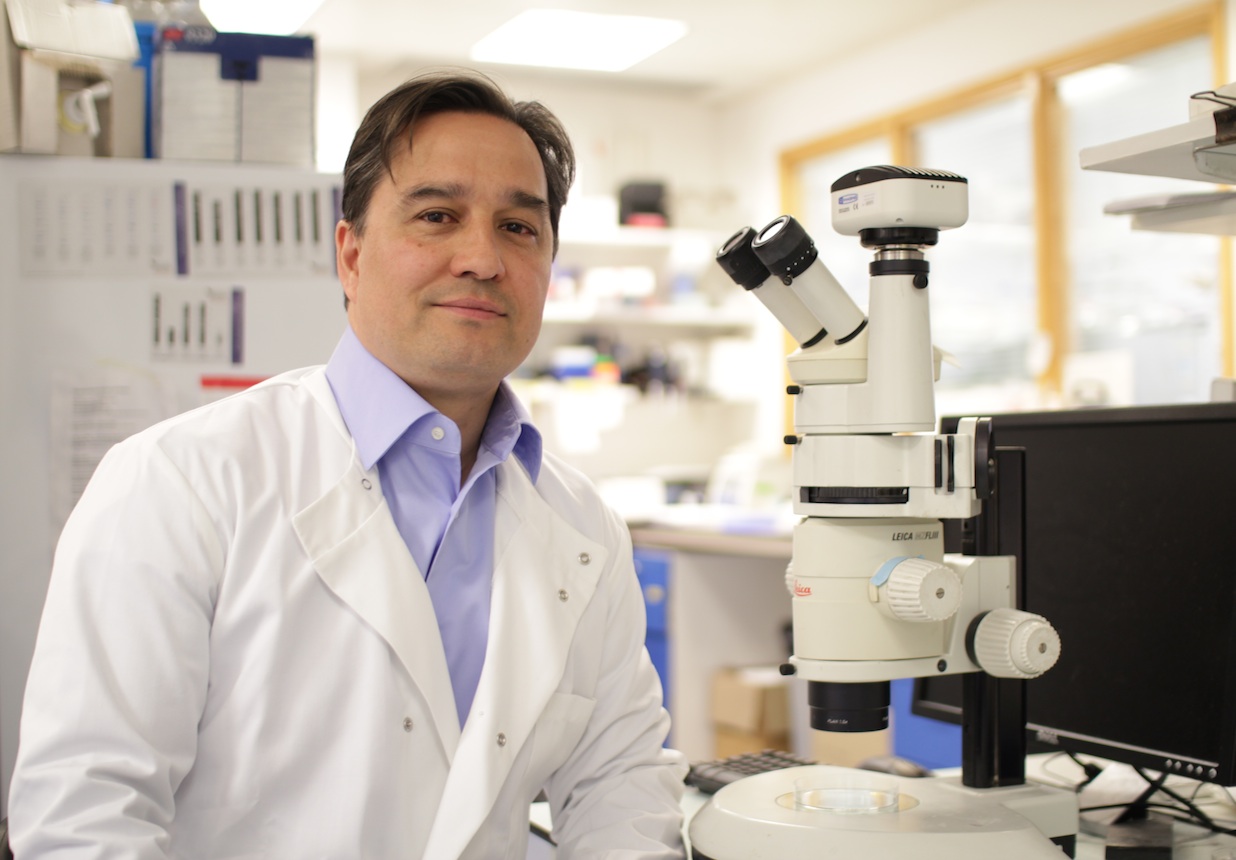

“Seeing with our skin” was created by Dr Mariya Moosajee, Consultant Ophthalmologist at Moorfields Eye Hospital and Senior Lecturer at UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, specialising in Genetic Eye Disease, and Meike Walcha-Lu, film-maker for the NIHR Moorfields BRC.